With second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in full bloom, we look at what new pandemic might lie just over the horizon.

The planet has experienced far worse pandemics than COVID-19. Other than the Black Death and European plagues, where epidemiological data is understandably spotty; Russian, Spanish, Asian and Hong Kong Flu have all ranked in the top 5 most deadly, each accounting for over a million deaths.

Of all of these, the Hong Kong flu pandemic which, scourged South Asia in 1968, killing over 1 million people is probably the least well known. Over half a century and three more flu epidemics later, Hong Kong is reknowned³’⁴’⁵’⁶ as the global epicentre of new strains of human and avian influenza viruses.

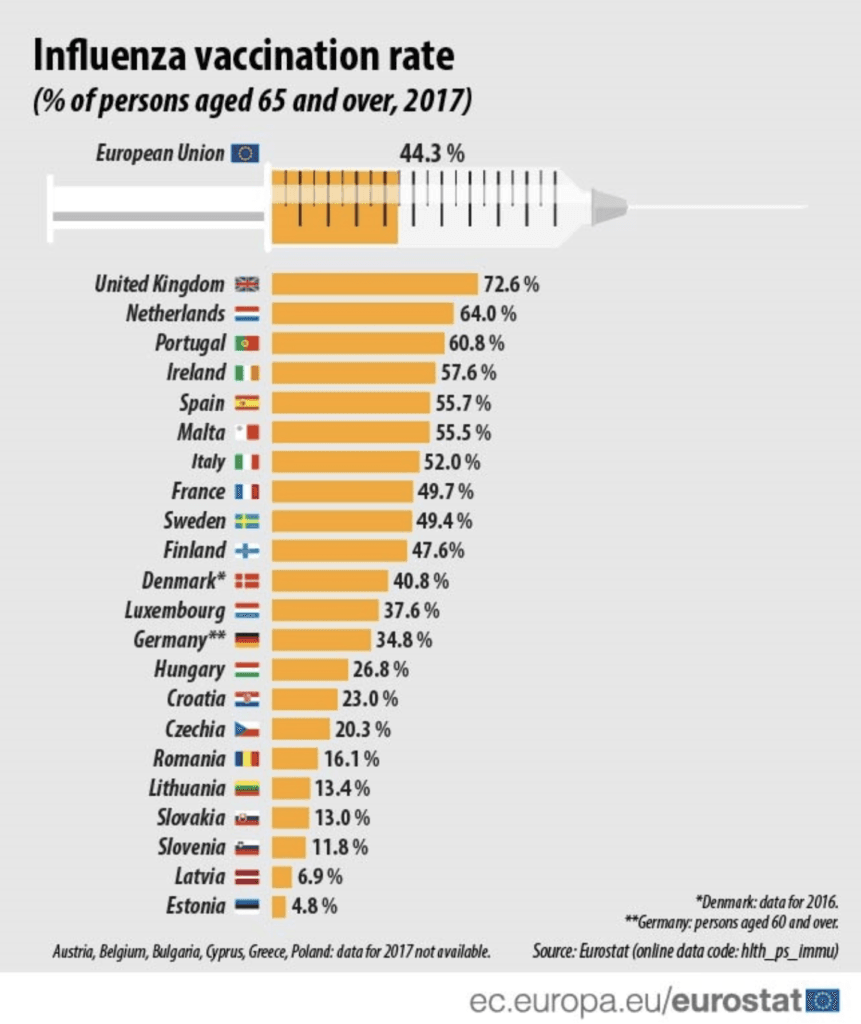

Europe seems to have learnt from its 1918 lesson. Since 2010, the EU has instigated a 75% vaccine target of at-risk patients, utilising a more comprehensive range of healthcare professionals to reach the target. Hong Kong seems behind the curve, relying on doctors and nurses under supervision, vaccination rates have stagnated at around 29%², with at-risk patients aged 16-64 at merely 13.9%¹⁰. These figures in comparison to other high-income, densely populated areas, is staggeringly low.

With climate experts predicting higher temperatures than ever this year, epidemiological experts say Influenza Type A which accounts for 80% of all influenza hospital admissions in Hong Kong will be on the rise⁶. So how can Hong Kong take a proactive approach and prevent yet another pandemic?

The threat of pandemic should not be minimised, nor should governments be lulled into a false sense of security.

K.F. Shortridge, The next influenza pandemic,University of Hong Kong, 2003³

Inaccessible prophylaxis.

Patient vaccine accessibility has been identified as a critical factor⁴ in causing low levels of flu vaccine uptake in Hong Kong. It has been shown that over 50% of at-risk patients do not know where they can access the influenza vaccine, and those that know where to get the vaccine nearly 40% would have financial difficulties to access the vaccine⁷. One major study⁸ indicates that although public clinics offered free flu vaccinations to the chronically ill patients, some participants believed that time inaccessibility of these clinics was a problem for them, especially for those who had to work. As one participant remarked:

“I know I can receive a free flu vaccine in public clinics, but I need to work for the entire day, and the service hours of the public clinics just cannot match with my work schedule. It’s silly to take a leave [from my work] to do the vaccine.”

Financially prohibitive.

Although the Hong Kong government provides free influenza immunisations to at-risk people, the cost of vaccination due to private doctor charges is still a dissincentive to at-risk patients⁸. One patient remarked:

“I do not have time to go to public clinics just for the vaccination, since I need to work. The only option for me will be private doctors, but I have to pay. I have no motivation to pay for an optional vaccine which seems not to be safe. It’s not worth paying, since I need to run the risk.”

Vaccine cost and availability are the main factors prohibiting the most vulnerable in Hong Kong from accessing a low-cost vaccine which has been proven to massively reduce public health spend. Furthermore, with a new COVID vaccine on the horizon, the Hong Kong government needs to ask itself a question which many countries have already answered. How can the public access a cohort of readily accessible healthcare professionals who are on every high street of the special administrative area to administer more vaccines?

Allow other healthcare professionals to administer vaccines.

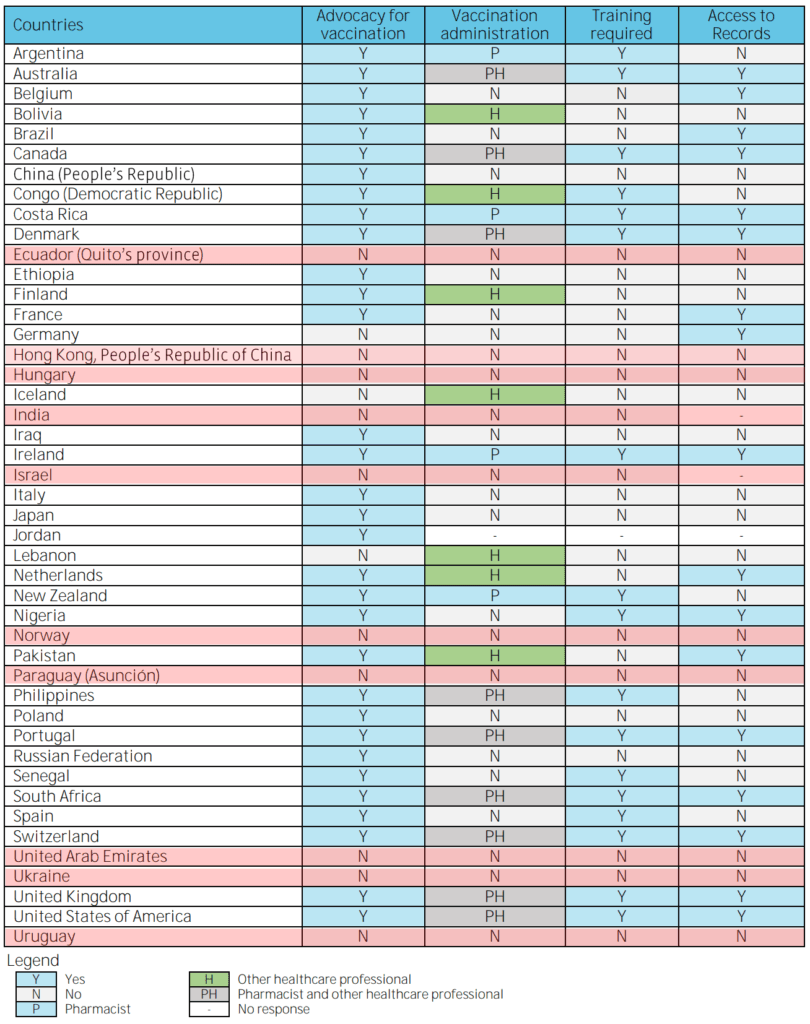

According to the FIP, which in 2016 surveyed 44 countries, reported that there are now only 24 countries which do not allow non-doctors to vaccinate patients. From all respondents, 71% (32 countries and territories) reported some level of engagement in support and advocacy activities connected with expanding immunisation service provision.

The data above shows that the special administrative area of Hong Kong seems to sit alongside countries such as Paraguay, Ukraine and India in not allowing pharmacist to vaccinate patients. There are many reasons for this, one is that current legislation does not define the roles and responsibility for pharmacists in this area and that there was limited acceptance and support from other healthcare professionals.

So what are the rate limiting steps to pharmacist vaccinators in Hong Kong?

All occupations are protective of the financial rewards which are specific to their professions and doctors are no exception. The Medical profession’s strongest non financial arguement is also correct, to an extent; healthcare needs to provide patients with only the best care, however, doctors no long hold this as a monopoly. Best practice has been proven amongst pharmacists for almost a decade.

Are pharmacists competent enough?

The largest systematic review and meta-analysis to date¹², included of thirty-six studies was conducted by Professor Jennifer Isenor at Dalhousie University Canada in 2016. The study shows conclusively that pharmacists vaccine immunisation standards were on par with their doctor colleagues and their expanded role led to a increased uptake of immunisations across the board.

Is it worth it?

Epidemiological studies show consistently a relationship between the presence of influenza virus and increased mortality rates, rates of hospital admissions, and health services utilisation. The greatest burden of illness from influenza occurs in the elderly who are at increased risk of death and other serious complications related to influenza. By training healthcare professionals to international best practice and allowing them to admnister vaccines we estimate that over $10 millon HKD can be saved annually.

Is it too late?

It is not too late to act, the influenza season in Hong Kong starts in November, its been said that to get ready, vaccines must be administered at least two weeks before⁷. As a minimum we recommend the Hong Kong government:

- To update their “Preparedness plan” from 2014 which should detail out what if anything can be done this year to mitigate potential increased risks⁹.

- Adopt proven, best practice training protocols and encourage the private sector to create a “reserve” of health professionals that can potentially handle the increase influenza vaccine demand and bolster potential capacity when a COVID-19 vaccine arrives.

References

¹Sino Biological, Hong Kong Flu (1968 Influenza Pandemic).

²Hong Kong third wave: with Covid-19 set to meet winter flu, let nurses and pharmacists call the shots. South China Morning Post, published, 25 Sep, 2020.

³The next influenza pandemic: lessons from Hong Kong. K.F. Shortridge, J.S.M. Peiris and Y. Guan, Journal of Applied Microbiology, 94, 70S–79S, Department of Microbiology, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China. Published in 2003.

⁴An influenza epicentre? Shortridge KF, Stuart-Harris CH. Lancet;(ii):832-813. Published in 1982

⁵Excess Hospital Admissions for Pneumonia, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, and Heart Failure During Influenza Seasons in Hong Kong. Journal of Medical Virology 73:617–623. Published in 2004.

⁶Seasonal Influenza Activity in Hong Kong and its Association With Meteorological Variations, Journal of Medical Virology 81:1797–1806, Paul K.S. Chan,1,2* H.Y. Mok et al. Published in 2009.

⁷Cross-sectional and longitudinal factors predicting influenza vaccination in Hong Kong Chinese elderly aged 65 and above, Paul K.S. Chan et al, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Journal of Medical Virology 81:1797–1806. Published in 2006.

⁸The perceptions of and disincentives for receiving influenza A (H1N1) vaccines among chronic renal disease patients in Hong Kong. Judy Yuen-Man Siu PhD MPhil BSSc Centre for Health Behaviours Research, School of Public Health and Primary Care, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China. Accepted for publication 12 June 2011

⁹Preparedness for Influenza Pandemic in Hong Kong Nursing Units. Agnes Tiwari, Marie Tarrant, Kwan Hok Yuen, et al. Journal of Nursing Scholarship., 2006; 38:4, 308-313. SIGMA THETA TAU INTERNATIONAL. Published in 2006.

¹⁰Seasonal influenza vaccine uptake among Chinese in Hong Kong: barriers, enablers and vaccination rates, Kai Sing Sun. Journal of Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics Volume 16, 2020

¹¹An overview of current pharmacy impact on immunisation. International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP). Ian Bates at al. Published in 2016.

¹²Impact of pharmacists as immunizers on vaccination rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Vaccine 34(47)Dalhousie University Halifax, NS. Published: October 2016